Artist v. Artist

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Lynn Goldsmith Et. Al.

Fair Use broadens in Artist Works

A recent court decision in the Second Circuit solidified the expanding and evolving scope of fair use in appropriation art, showing that obtaining a license to use other copyrighted works as artistic inspiration is not always necessary. In the opinion, published on July 1, 2019, Manhattan Federal Judge John G. Koeltel held that Andy Warhol’s use of a photograph of Prince as “source art” is fair use and requires no license, credit or compensation to the original photographer.

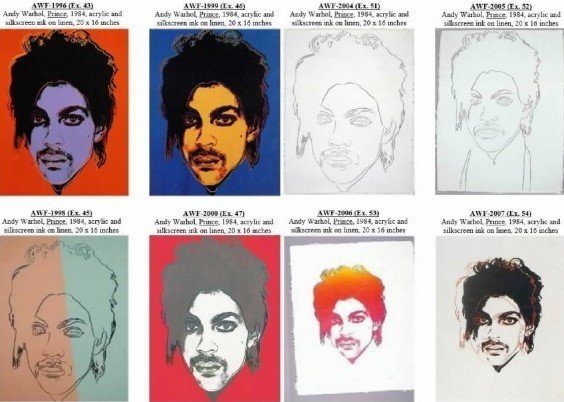

Original Warhol works

Original Warhol works

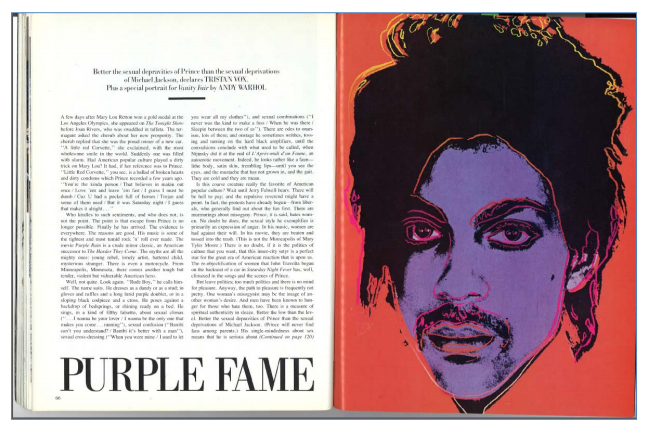

The history of the case is as follows. In 1984,Vanity Fair obtained a $400 license from celebrity photographer, Lynn Goldsmith, to supply her portraits of Prince as source art to another artist for one of their upcoming articles, none other than Andy Warhol. Warhol took the portraits Goldsmith had taken of Prince years prior and used them as inspiration to create sixteen new works – twelve silk-screen paintings, 2 screen prints on paper, and 2 drawings. In classic Warhol fashion, the works cropped the original photo and added bright, unnatural coloring to Goldsmith’s black and white originals. One of the pieces was chosen to accompany a Vanity Fair article about Prince titled “Purple Fame,” and the magazine included a small source credit to Goldsmith.

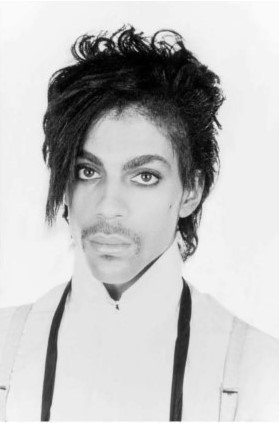

Above: Goldsmith’s portrait; 1984 Vanity Fair article

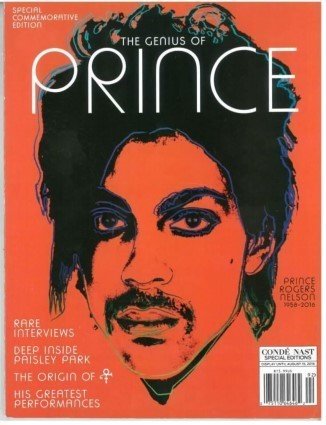

When Prince passed away in 2016, Vanity Fair republished the Warhol work; this time, without a license and without giving credit to Goldsmith. According to Goldsmith, it was not until this 2016 republication that she became aware of the Warhol works based on her photograph. Soon after, Goldsmith notified the Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF), which manages Warhol’s works, sharing that she believed there had been an infringement of her copyright. In disagreement, AWF filed a motion for declaratory judgement that the Warhol works do not constitute copyright infringement under the affirmative defense of fair use. She counter-sued for infringement.

Vanity Fair 2006 reprint of Warhol’s work

According to Goldsmith, her black and white portraits were intended to capture Prince’s vulnerability and demeanor as “not a comfortable person.” Meanwhile, the court found that the Warhol works transforms Prince “from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure.” Such transformation is essential to the outcome of this case.To analyze a fair use defense and allow for circumvention of traditional copyright requirements, courts will balance the following factors (The Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. §107):

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

In the decision, Judge Koeltel emphasized that the more transformative a work is, the less important each factor becomes and the more likely it is that a work is covered by fair use. In this case, the purpose and character of Warhol’s work was to accompany a commercial article discussing Prince’s fame – not his vulnerability. The purpose of the work was so transformed that the works are not substantially similar or likely to be confused. Similarly, although substantial use of an original can weigh against a finding of fair use, the court emphasized that a transformative work, by nature, needs to copy a substantial amount of the original in order to transform it, justifying Warhol’s substantial use of Goldsmith’s work as source art.Ultimately, while the Warhol works in this case merely cropped and added colors to Goldsmith’s original portrait, the court found that the overall result was transformative such that there was no copyright infringement issue. Giving rise to public controversy, the court also considered factors outside of fair use, such as the public benefit of having access to Warhol’s works and the fact that Warhol’s works are immediately recognizable as his own.Fair use is decided on a case by case basis, no two cases are alike. How one judges whether a use is transformative and non-infringing or derivative and infringing can be a close call. It is helpful in comparing works to consider the following. Is the purpose of the final product or project similar to the original? How much of the copyright-able elements (e.g., lighting, positioning, imagery, etc.) of the original will be retained? Would the other work create legitimate and direct market competition to the original work, including a license for a derivative? If the new use is a work of visual art and does not retain much of the underlying copyright-able elements of the original, it is likely that the use will be considered transformative and non- infringing, especially if created by Warhol.______________________________________________________________________To read the full case, see: https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/new-york/nysdce/1:2017cv02532/472094/84/